The History of Chocolate: from Sacred Cacao Fruit to Industrial Chocolate Production

On this page, we take you through the fascinating history of chocolate. You will discover how a simple fruit from the rainforest grew into a globally beloved product. From sacred drink among the Maya to industrial production in modern factories – the story of chocolate is one of discovery, tradition, and technological progress.

The Origins of Cacao: the Beginning of Global Chocolate History

The earliest traces of chocolate date back thousands of years, deep in the rainforests of South America. There began the story of a fruit that would one day conquer the world.

Long before cacao became a drink of the gods among the Maya or ended up in luxury chocolate bars in Europe, the cacao plant was already growing deep in the Amazon and Orinoco regions of South America. Archaeologists in Ecuador (Santa Ana-La Florida) found traces of fermented cacao residues on pottery dating back more than 5,000 years. This shows that the use of cacao goes back to the Mayo-Chinchipe culture, long before the rise of the classical civilizations in Mesoamerica.

Although we do not know exactly how cacao was consumed at the time, traces of fermentation and residues indicate deliberate processing of cacao beans — possibly as a drink, medicine, or for ritual purposes.

Ritual cacao beverage and status among the Maya: the spiritual beginning of chocolate

For the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica, cacao was more than just food – it was a key to the divine.

Long before cacao played a role among the Maya and Inca, it was already used by the Olmecs, an early civilization in present-day Mexico (ca. 1500 BC – 400 BC). Archaeological findings show that Olmec priests were sometimes buried with cacao beans – presumably as an offering to the gods or as spiritual provisions for the afterlife. This underlines how deeply cacao was rooted in ritual, religion, and conceptions of life after death.

From around 250 AD — during the Classic Maya period — images also appear of priests and kings offering cacao during ceremonies, funerals, or sacrifices. The beans were fermented, roasted, and ground into a bitter drink, often enriched with chili, flowers, or spices.

According to ancient traditions, cacao was believed to induce visions or spiritual insights. This was likely due to the combination of theobromine and caffeine in cacao, along with herbs or plants with mild hallucinogenic effects. In the right dosage – and within a ritual setting – it could lead to an expanded consciousness: an experience seen as contact with the divine.

The drink was reserved for a small group with a special social role. Warriors drank cacao to increase their strength and endurance for battle. Priests used it in rituals, to achieve spiritual purification and establish contact with the divine. And for kings, it was a symbol of power, status, and divine origin.

Cacao was so valuable that it also served as currency. Only the elite – kings, warriors, and priests – were allowed to use it.

Chocolate was once sacred. What began as a ritual grew into a global passion.

The Introduction of Chocolate in Europe: from Aztec drink to European delicacy

From drink of the gods to European status symbol – from an Aztec emperor to a Brussels apothecary.

In 1519, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés set foot on the shores of present-day Mexico. His goal: gold and glory for the Spanish Empire. But alongside precious metals, he also discovered something unexpected – cacao. Among the Aztecs, this bitter drink played a central role in ceremonies and daily rituals. According to tradition, Emperor Montezuma drank dozens of cups of this powerful cacao beverage every day, served in golden goblets.

Cortés brought cacao beans and knowledge of their preparation back to Spain, probably around 1528. At first, the drink was regarded as medicinal or exotic. Only when sugar, cinnamon, and milk were added did a sweeter, more accessible version emerge, which became popular among the European elite.

An important step in this development is attributed to Sir Hans Sloane, an English physician who stayed in Jamaica around 1687. He found the local cacao drink too bitter and added milk and sugar – a combination he described as “pleasant and nourishing.” Back in England, he introduced the drink, which was later sold as milk chocolate in pharmacies, forming the basis for the later commercial chocolate drinks of brands such as Cadbury.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, cacao spread further to Italy, France, England, and the Low Countries. In monasteries, courts, and salons, hot chocolate drinks became a symbol of style and refinement. Apothecaries and confectioners began processing cacao, and in England, Switzerland, and later Belgium, the first chocolate workshops and factories were established.

A fine example of this combination of medical origin and culinary creativity can be found in Belgium:

Jean Neuhaus Jr., the grandson of a Brussels apothecary, created a world first in 1912. His family had originally used chocolate to make bitter medicines more palatable. Jean Jr. took it a step further and created the first filled praline: a hollow chocolate shell with a soft filling.

The result? A new form of chocolate experience, and the beginning of modern dosing of filled products – a technique still applied worldwide today.

The Cacao Belt: origin and climate influence on the flavor of chocolate

Not all cacao tastes the same – and that has everything to do with climate, soil, and variety.

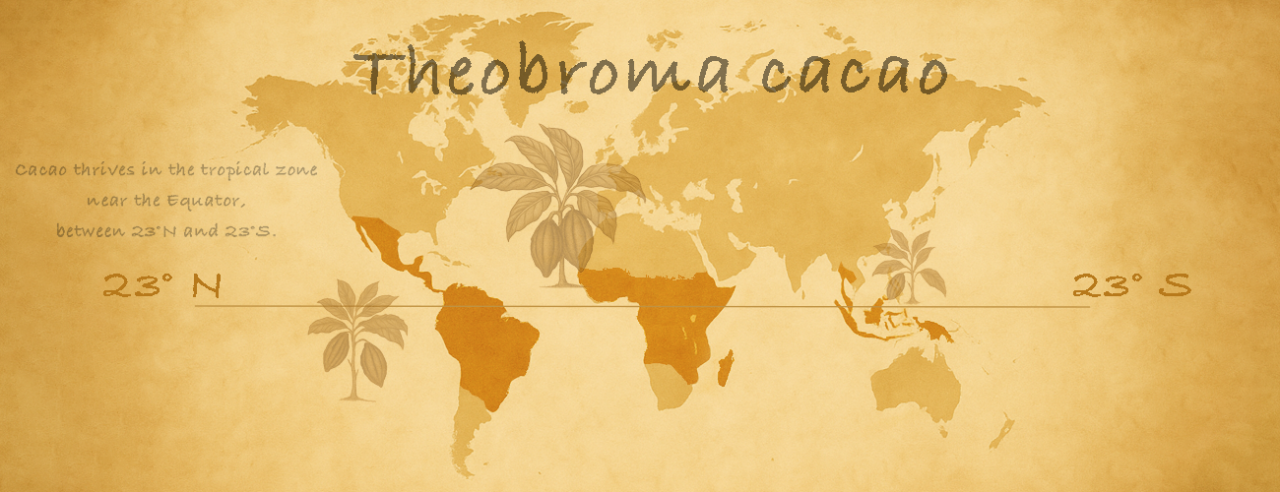

The cacao tree is officially called Theobroma cacao, which literally means “food of the gods” (theo = god, broma = food). The name was coined in the 18th century by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, referring to the sacred status of cacao in ancient civilizations such as the Maya and Aztecs.

Cacao plants grow only in regions around the equator – between 23° north and south latitude – because they need a humid tropical climate. The largest producers are in West Africa (Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon), Latin America (Ecuador, Brazil, Peru) and Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Philippines).

But just like with wine, the soil, climate, altitude, and variety also determine the final flavor of cacao. A bean from Madagascar tastes fruity and acidic, while cacao from Ecuador can be more floral or nutty. Chocolatiers and producers increasingly take this into account, consciously choosing specific single-origin cacaos or blends – depending on the desired flavor profile.

The origin of cacao helps define the character of chocolate – from intense and powerful to subtle and aromatic.

Industrial chocolate production: from craft to mass production

New machines, old love – chocolate suddenly became available to everyone.

The 19th century brought a breakthrough in the processing of cacao. Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, new machines appeared that could produce chocolate more cheaply, more consistently, and in larger volumes. In 1828, Coenraad Johannes van Houten in the Netherlands developed the cocoa press, which separated fat (cocoa butter) from cacao mass. This paved the way for powdered cocoa and better control over texture and flavor.

Initially, the remaining cocoa butter was considered waste. In a chocolate factory in Bristol (J.S. Fry & Sons), the fat caused so many problems when being flushed away that the company repeatedly received fines for dumping it. Until Joseph Fry, in 1847, came up with the idea of mixing cocoa powder again with part of the cocoa butter and sugar. The result? A mixture that hardened into the first edible chocolate bar. A discovery that would forever change the chocolate industry.

Across the ocean, Milton Hershey played a similar pioneering role. At the beginning of the 20th century, he introduced a new version of milk chocolate in the United States – inspired by Swiss recipes, but adapted to the American taste. His vision? To make quality chocolate affordable for everyone. In 1903, he built an entire town around his factory in Pennsylvania, complete with schools, hospitals, and housing for his workers.

The name Hershey grew into an icon of American chocolate – and his industrial approach set the tone for the further commercialization of chocolate worldwide.

Later, Rodolphe Lindt in Switzerland introduced the conching machine (1879), which allowed chocolate to be stirred and rolled for long periods until it became a smooth, melting mass. This technique gave chocolate its recognizable velvety mouthfeel and became the new standard of quality.

Belgium also developed during this period into an international center for chocolate processing. Belgian chocolatiers became known for their refined flavor combinations and attention to finishing. In 1915, Louise Agostini, wife of Jean Neuhaus Jr., designed the first ballotin box – an elegant cardboard packaging that protected pralines from breaking or deforming. The box not only provided a practical solution but also became a symbol of care and quality – a standard still used worldwide today.

An important Belgian pioneer from that period was Callebaut, founded in 1911 in Wieze. Originally starting as a brewery, the company soon shifted to chocolate production for bakers and pastry chefs. Callebaut became known for its consistent quality and innovation in recipes. The factory in Wieze grew into one of the most modern chocolate factories in Europe – and today it remains the largest chocolate factory in the world.

On the French side, around the same time, Cacao Barry was founded in 1842 by Charles Barry, a French businessman who, after a trip to Africa, started cacao import and processing. The company became a pioneer in the selection of quality cacao and the refinement of flavors for top chocolatiers.

In 1996, the two iconic brands merged into one powerful group: Barry Callebaut. The company combines the Belgian craftsmanship of Callebaut with the global sourcing expertise of Cacao Barry. Today, Barry Callebaut is active in more than 30 countries, supplies both industrial producers and artisanal chocolatiers, and continues to invest in innovation, sustainability, and education through initiatives such as the Chocolate Academy.

What once was handwork for priests or apothecaries was now refined by machines – with companies like Barry Callebaut as global pioneers, rooted in Belgian and French traditions.

From chocolate craftsmanship to automation in modern production

The love for chocolate remained, but the way of production evolved.

Where chocolate used to be entirely tempered, moulded, and filled by hand, today modern machines provide greater precision, efficiency, and control. Yet the craftsmanship has not disappeared – it has simply adapted to the needs of today.

Today, there are many degrees of automation. Some chocolatiers deliberately choose an artisanal approach, but still make use of basic equipment such as melting tanks, manual tempering machines, or simple dosing guns. Fully manual tabling on marble surfaces, as in the past, has become increasingly rare due to time and efficiency constraints.

At the other end of the spectrum are larger production companies, working with fully automated lines to make thousands of products per hour. These systems combine melting, tempering, filling, decorating, and cooling in one continuous process line – without compromising product quality.

Thanks to technological progress, there are now solutions for every level: for any scale of production — depending on the target market. Machines for melting, tempering, moulding, coating, dosing, or decorating support the craftsmanship of the chocolatier – whether starting small or thinking big.

A fine example of how tradition and technology can go hand in hand is Belcolade. This Belgian brand, founded in 1988 by Puratos, focuses on high-quality chocolate for professionals – with 100% Belgian production in Erembodegem. Through programs such as Cacao-Trace, the brand strongly promotes sustainable cacao cultivation, fair trade, and controlled flavor profiles, supported by modern installations. In this way, Belcolade shows that automation and craftsmanship do not have to be mutually exclusive.

Chocolate remains a craft – but one that today is supported by technology growing alongside the ambitions of the maker.

Chocolate then and now: from ritual drink to the global chocolate industry

Chocolate has taken many forms through the centuries, but its soul has remained intact.

What began as a sacred drink has grown into a worldwide icon of indulgence, comfort, and flavor. But chocolate is more than just a treat. Cacao contains compounds such as theobromine and phenylethylamine, which stimulate the release of dopamine and serotonin – chemicals that make us feel happy, relaxed, and even in love. It is no coincidence that people turn to chocolate in times of stress, sadness, or romance.

And yes: dark chocolate with a high cacao content also contains antioxidants and can, in moderation, contribute to a healthy diet. In some cultures, cacao was even considered an aphrodisiac for centuries – a substance believed to stimulate libido. While science has nuanced views on this, chocolate remains associated with seduction, romance, and pleasure to this day.

Today, chocolate production stands at a crossroads of tradition and technology. At Betec, we understand that balance. Our machines are designed to combine modern efficiency with artisanal finesse – so that every maker, large or small, can share their passion with the world.

Thousands of years after its discovery, chocolate still inspires – not only through its flavor, but through the emotions it awakens in those who taste it.

Frequently Asked Questions about Chocolate (FAQ)

1. Is white chocolate really real chocolate?

White chocolate contains no cocoa mass – the dark, aromatic part of the cocoa bean that gives dark and milk chocolate their typical flavor. However, it is made with cocoa butter, the valuable fat of the cocoa bean. According to European law, a product may only be called white chocolate if it contains at least 20% cocoa butter.

Artisanal white chocolate often has a higher cocoa butter content, giving it a rich, creamy flavor, while industrial chocolate sometimes replaces part of the cocoa butter with cheaper fats such as palm oil or shea butter.

2. Is Belgian chocolate better than other chocolate?

“Better” is subjective, but Belgium applies strict quality standards, often using only cocoa butter, precise tempering, and constant quality control. Combined with centuries of expertise, this explains why Belgian chocolate is globally renowned.

3. Where is the largest chocolate factory in the world?

In Wieze, Belgium – home to Barry Callebaut. This factory produces tons of chocolate daily for brands and professionals worldwide and also hosts the Chocolate Academy™.

4. Why does chocolate melt in your mouth but not in your hand?

Because cocoa butter melts at around 34°C, close to body temperature. This makes chocolate melt on your tongue but remain firm at room temperature. Proper tempering also gives chocolate its characteristic snap.

5. Was chocolate really used as medicine?

Yes! In the 17th and 18th centuries, cocoa was prescribed for fever, fatigue, depression, and digestive issues. It was even sold in pharmacies, including by the grandfather of Jean Neuhaus, who later invented the praline.

6. Why is Belgian chocolate often more expensive?

Because of premium ingredients, higher cocoa butter content, artisan finishing, and local production. Add to that its worldwide reputation, and Belgian chocolate is positioned as a refined, trustworthy product.

7. Is there a fourth type of chocolate besides dark, milk, and white?

Yes: ruby chocolate. Launched by Barry Callebaut in 2017, it is made from a specific cacao variety, has a natural pink color, and a fruity flavor – with no added coloring or flavorings.

8. Why is Belgium known worldwide as a chocolate country?

Because of its long tradition, technical precision, and quality standards. Belgians pioneered fine refining, tempering, and moulding. The invention of the praline (1912) and the ballotin box (1915) are uniquely Belgian contributions.

9. Why does chocolate sometimes turn dull or white?

That’s fat bloom or sugar bloom. When too warm, cocoa butter rises to the surface, leaving a white film. If cooled too quickly or stored in a humid place, sugar bloom forms. Proper tempering and storing at 16–20°C prevent this.

10. Does chocolate really make you happy?

Yes – not only because it tastes good. Chocolate contains phenylethylamine, theobromine, and caffeine, which stimulate the brain to release dopamine and serotonin – the so-called “happy hormones.”

11. Why is cocoa called “food of the gods”?

Because the botanical name is Theobroma cacao, which literally means “food of the gods.” Named in the 18th century by scientist Linnaeus, it honored the spiritual value cacao had for the Olmecs, Mayans, and Aztecs.

12. Do all types of chocolate use the same cocoa bean?

No. There are three main varieties:

- Criollo (aromatic, rare, expensive)

- Forastero (strong, bitter, most common)

- Trinitario (a hybrid, aromatic and robust)

The flavor of chocolate depends not only on processing but also on the genetic origin of the bean.

From the jungles of Ecuador to the workshops of Belgium: chocolate has always inspired people.

It is more than a product. It is culture, science, tradition, and innovation.

Whether you work by hand or seek technology to scale up your production: chocolate requires knowledge, precision, and passion. At Betec, we are committed to supporting those values – with machines that help you write your own chapter in this centuries-old story.

Thousands of years after its discovery, chocolate continues to surprise – in flavor, technique, and meaning.

Curious about what we can do for you?

At Betec, we help chocolate makers worldwide bring their ideas to life – with care, craftsmanship, and technology.